BEI Jiaxiang and the Mutual Shaping of Eastern and Western Aesthetics I

The flow of art has never ceased to intersect and exchange with civilization.

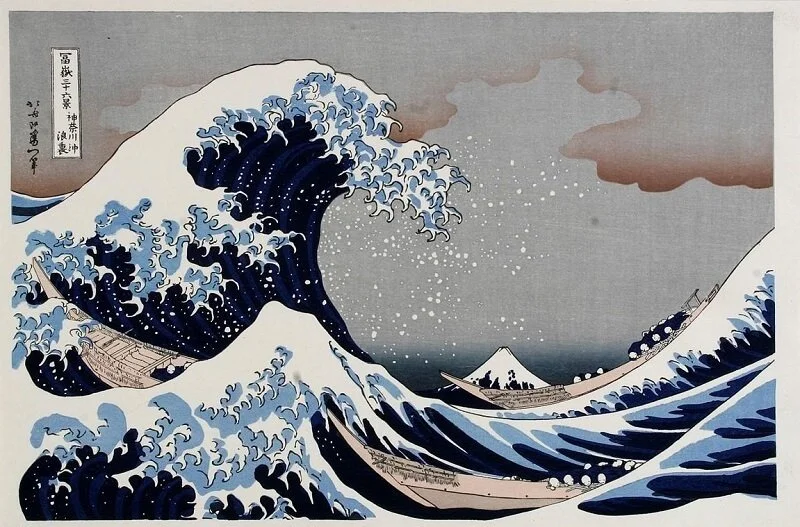

Great Wave Off Kanagawa

Japanese ukiyo-e Style Painting

Hokusai (1829-33)

Looking back to the mid-19th century, a subtle tide from the Far East arrived on the European shores, sparking an unprecedented wave of transformation in Western art history. Japanese ukiyo-e, with its distinctive visual language—flattened compositions, shadowless colour blocks, daring cropping, simplified yet expressive outlines, and vivid, decorative hues—opened a new window for Western artists mired in academic tradition.

Manet’s The Fiddler abandoned traditional three-dimensional modelling in favour of flat colour planes; Van Gogh not only copied Ukiyo-e but also transformed Katsushika Hokusai’s wave curves into the swirling night sky of Starry Night; Monet incorporated oriental symbolism into La Japonaise, while Degas found fresh compositional ideas through stage-like perspectives.

La Japonaise

Claude Monet

Oil on Canvas

231.8 cm × 142.3 cm

1876

At the core of this “Eastern influence on the West” movement lies ukiyo-e’s revolutionary visual grammar: it liberated rigid perspective, simplified complex light and shadow, bestowed aesthetic value upon lines themselves, and directed artistic focus toward vibrant, everyday life. However, from today’s perspective, this influence was largely superficial, as it only touched upon innovations at the formal level. The rich philosophical foundations of ukiyo-e—such as mono no aware (the gentle sorrow for objects) and Zen’s contemplative emptiness- had never truly become embedded in the creators’ core.

Having spent years abroad, BEI, in developing his own oil series like Hometown and Horses, often sensed this transcultural exchange as well. He shared with those Western masters inspired by ukiyo-e a steadfast dedication to transforming heterogeneous art forms into personal expressions. To him, although oil painting is a quintessential Western medium, it became the arena where he pushed the boundaries of Chinese aesthetic possibilities. He did not passively accept traditional oil techniques, but actively and boldly redefined its language in a highly individual way.

Winter Day - Hometown Series

158*103 cm

2016

In his series depicting memories of Shanghai, BEI relinquished the bustling, flamboyant colors characteristic of the colonial-era, instead immersing himself in a subtle yet rich symphony of grays. This was not a lack of color but a deliberate aesthetic choice—a conscious attempt to blend the philosophical essence of China’s ink wash art, specifically the concept of “five-shade of ink,” into the Western color system. The mottled walls of Shikumen houses, hazy silhouettes of qipao figures, and the misty aura of alleyway skies coalesced into poetic vignettes of history through layered tonal diffusions, evoking nostalgic memories buried deeply inside BEI.

When capturing fleeting moments of galloping horses, BEI fully liberated oil painting’s materiality. Using the sharp edge of palette knives, he created crack-like white streaks reminiscent of fractured stone; his mastery over the flow and accumulation of oil colors infused the brushstrokes with the unstoppable force of thunder. In Flicker in the Light, the fierce streaks left by the sweeping horse tails; and in Windy Avenue, the image of breaking free from all bridle restraints—all vividly demonstrate BEI’s relentless challenge to the expressive limits of oil painting. His deep exploration and redefinition of the medium’s potential echo the breakthroughs achieved by Impressionist masters who drew inspiration from ukiyo-e to seek novel artistic expressions.

Windy Avenue - Hometown Series

Oil on Canvas

91×73cm

2022

BEI Jiaxiang’s explorations can be viewed as a contemporary echo and variation of the historical wave of “Eastern influence on Western art.” Like his predecessors, he embraced heterogeneous cultural visions, boldly advancing a personal artistic language. Yet, beneath this outward pursuit of formal innovation, the soil of his Eastern origin cultivated a profound cultural consciousness—a desire to actively fuse formal experimentation with the core spiritual essence of his native tradition. This pursuit hints that, amid the ongoing dialogue of East and West in art, the Eastern path may be heading toward even deeper levels of ontological creation—possibilities rooted in an authentic, intrinsic cultural voice.