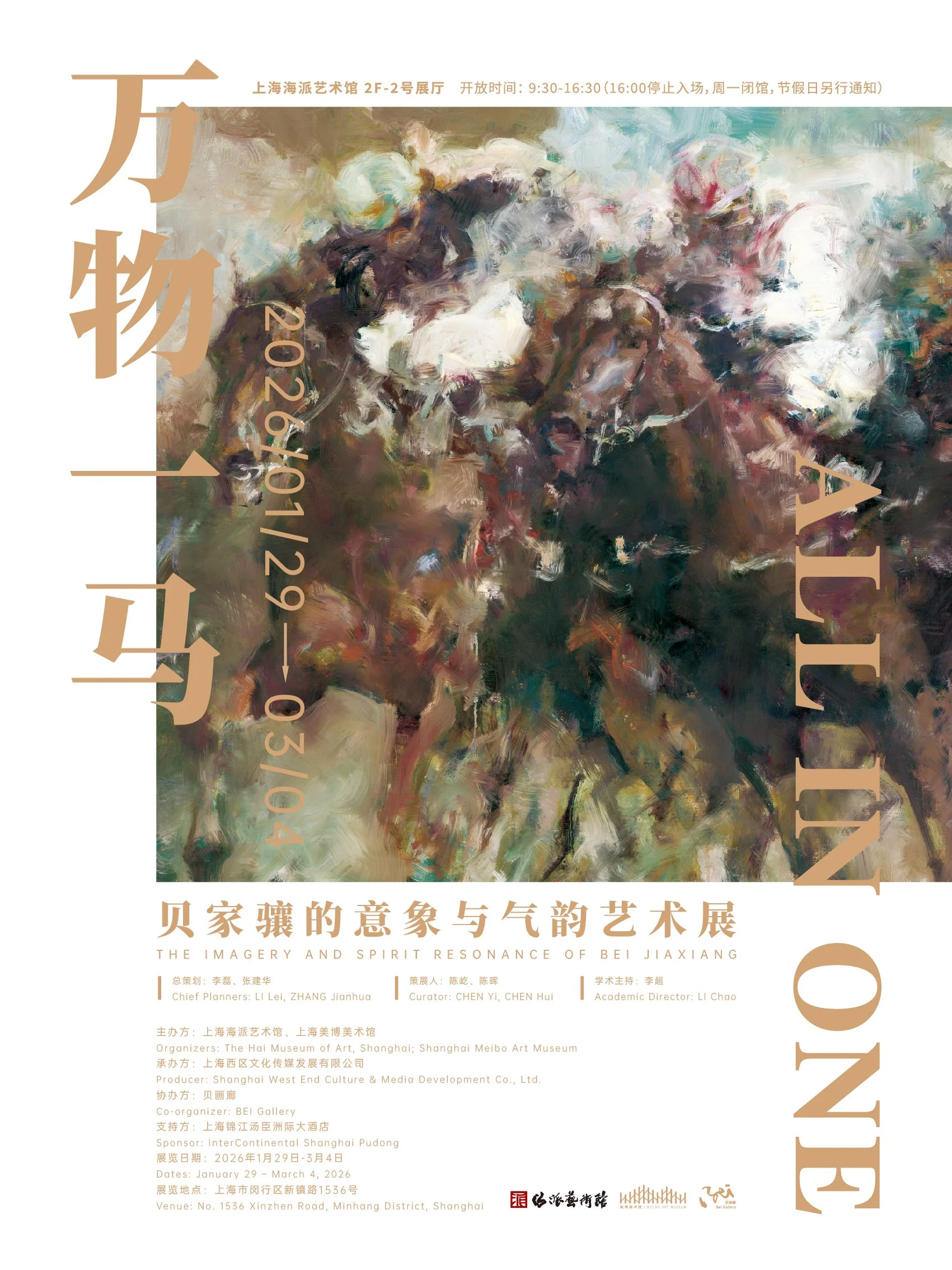

All-in-One

—The Imagery and Spirit Resonance of BEI Jiaxiang

Zhuangzi’s statement from the book On the Equality of Things: “Heaven and earth are one finger; the ten thousand things are one horse”(All in One)—is like an eternal pebble cast into the long river of Eastern thought, its ripples still poppling in the deep pool of Chinese aesthetics to this day. The power of this proposition lies not merely in the startling turn of phrase, but in its fundamental challenge to and transcendence of habitual perception. Inserting this ancient philosophical key into the vast artistic output of contemporary artist BEI Jiaxiang, we can glimpse a hidden door opening towards the core of his artistic spirit.

Surveying BEI’s painting practice spanning over forty years, his art can be understood as a contemporary visual response to and methodological enactment of the concept of “the equality of things.” Though his subjects are broad—varying from steeds to urban scenes, to opera, figures, and flowers—their internal unity stems precisely from a particular way of seeing: one that does not aim for the endpoint of representing the superficial differences between objects, but takes as its goal the capturing of the intrinsic life-force, the spirit-resonance that governs all things. Zhuangzi considered the horse a metaphor for flux, a state of unbridled motion, the vital, self-so life itself, not fixed by human concepts. BEI’s passion for horses, and indeed his very impulse to create, is precisely a release and celebration of this primordial life-energy. Whether it is the tremor of muscles in galloping horses, the shifting play of light and shadow on old Shanghai streets, the arrested power in the posture of an opera character, or the vibrant rhythmic vitality emanating from figures and flowers, all things under his brush are infused with the same “living impulse.”

Thus, BEI has attempted to build a bridge: bringing the ancient proposition of “spirit-resonance life-motion” from Chinese aesthetics into a richly Shanghai-School-Art-Style romantic, cross-cultural dialogue with the Western pursuit of painting’s autonomy and internal truth since the modern era.

Firstly, BEI’s practice manifests in the liberation of “form.” He does not pursue static completeness of image, but focuses on the process of an image’s generation and its state of presence. To this end, he often employs brushwork that omits details and accentuates dynamic momentum, allowing the brushstroke itself to surpass its descriptive function and become a direct inscription of the mind’s trace. This technique shares a formal affinity with what Wölfflin described as the Baroque “painterly” (malerisch) visual tendency—abandoning clear contours in pursuit of a tremulous fusion of the visual whole. Yet its spiritual roots lie closer to the Chinese aesthetic tradition of “transcending form to capture likeness.” BEI’s deconstruction and recombination of imagery actually mirrors Zhuangzi’s dismantling of conventional cognitive patterns: the first impression of a painting may still be a horse, a person, a flower; yet upon sustained gazing, the specific physical form gradually dissipates, replaced by a haze of time, an intensity of emotion, and an eruption of life. The concrete “thing” dissolves, the universal “idea” emerges—this is the visual realisation of “the equality of things”: stripping away names and appearances to perceive the fundamental truth directly.

Secondly, BEI liberates colour from mere descriptive function, bringing it into the realms of phenomenology and emotion. Take the Old Shanghai series as an example: the interweaving of grey-blues, warm golds, and deep reds is not a scientific record of the sky’s light at a specific moment, but a shaping of psychological time—of “memory” itself. Colour here becomes the equivalent of time’s texture: vague yet warm, both clear and hazy, just as memory itself intertwines certainty with reverie. This tendency recalls Monet’s late immersion in light and colour, yet BEI’s colour carries a greater weight of historical psychology. As T.J. Clark noted, modern painting made colour a central medium of experience; BEI goes further, transforming colour into a visual vessel condensing historical time and the collective unconscious. He advances the Shanghai School’s artistic intuition regarding the sensitivity to “modern time” into philosophical expression. The Shanghai School, born of treaty-port culture, inherently possessed a knack for capturing the instantaneity of urban life; BEI’s “Old Shanghai” imbues this theme with profound emotional depth. With the painter’s bodily sensibility, he translates the urban psychology described by Georg Simmel—the fragmentation of sensation and nostalgic sentiment—into a lyrical epic about loss and preservation. That very ambiguity of colour and brushstroke is not an escape, but rather an aesthetic strategy to resist temporal entropy: solidifying the fleeting instant into an eternal image.

Going further, from a cultural theory perspective, BEI’s practice can be situated within the framework of what Homi Bhabha termed the “Third Space.” Two traditions meet in that interstitial zone, becoming neither one nor the other, but generating a creative sense of hybridity. BEI Jiaxiang’s brushwork is neither wholly Western Expressionist automatism nor a simple transplantation of traditional calligraphy; on the canvas as an “interstice,” he facilitates a mutual transformation of Chinese and Western aesthetic traditions, becoming an on-site expression of constructing a culturally hybrid identity within a globalised context.

Ultimately, all this converges into a contemporary representation of the most core aspects of the Shanghai School spirit: its civic nature and secular vitality. The life force of Shanghai School art lies in its embrace and poetic distillation of vivid reality. Whether depicting the bustle of city life, the fullness of the human body, or the exuberance of flowers, BEI’s brush is filled with a warmth that affirms the present and celebrates life. This artistic tenor resonates both with Zhuangzi’s equalising gaze and with the West’s celebration of the “this-worldly” and the “human body” since the Renaissance. His paintings thus connect local cultural memory with universal human feeling, allowing highly localised subjects to touch the most common of human emotions.

Therefore, this exhibition is not merely a retrospective of one artist’s personal journey and oeuvre, but also a potent testimony to the continued vitality of the Shanghai School—this local cultural gene—within the context of contemporary art. What the exhibition seeks to present is not just a chronological sequence of works or the evolution of technique, but rather, through a representative selection of paintings, to reveal an enduring aesthetic attitude: seeking the universal rhythm of life within a world of proliferating appearances, and preserving the warmth of collective memory within fragments of history. Through his practice, BEI Jiaxiang declares that the Shanghai School is not merely a historical term, but a forward-facing spiritual stance full of creative potential—one that, under the grand vision of All in One, dares to encompass ancient and modern, Chinese and Western, transforming all into deeply felt and moving poetry of life. Here, viewers may find both the echoes of local history and feel that artistic resonance which transcends context to touch the universal.