“The fragments of memory are not forgotten but lie dormant.”

— Marcel Proust

Landmarks of My Hometown

-

The Bund in May

Oil on Canvas

200×220 cm

2017

-

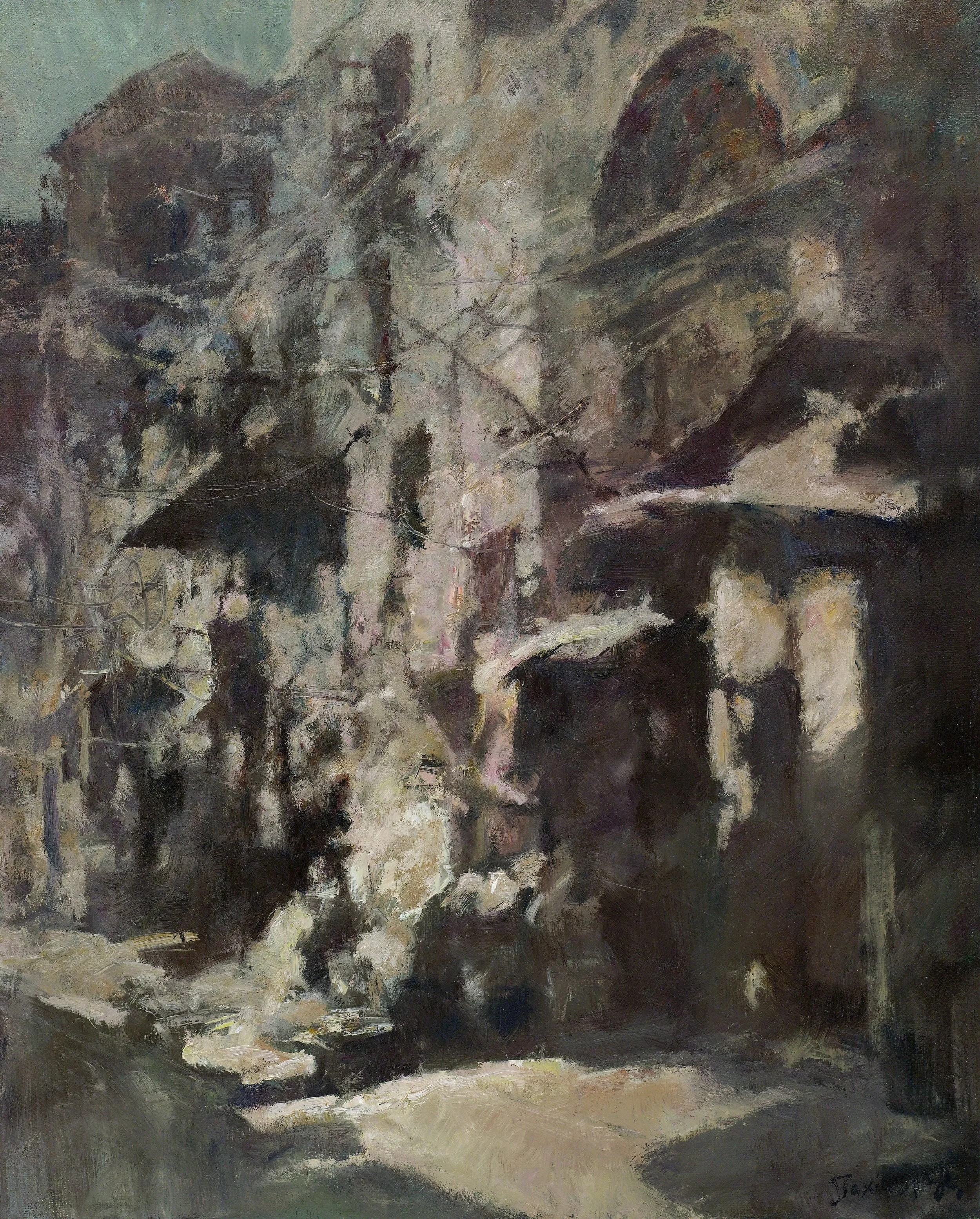

The Glittering Hongkou

Oil on Canvas

116×116 cm

2016

the Film-Like Old Time

-

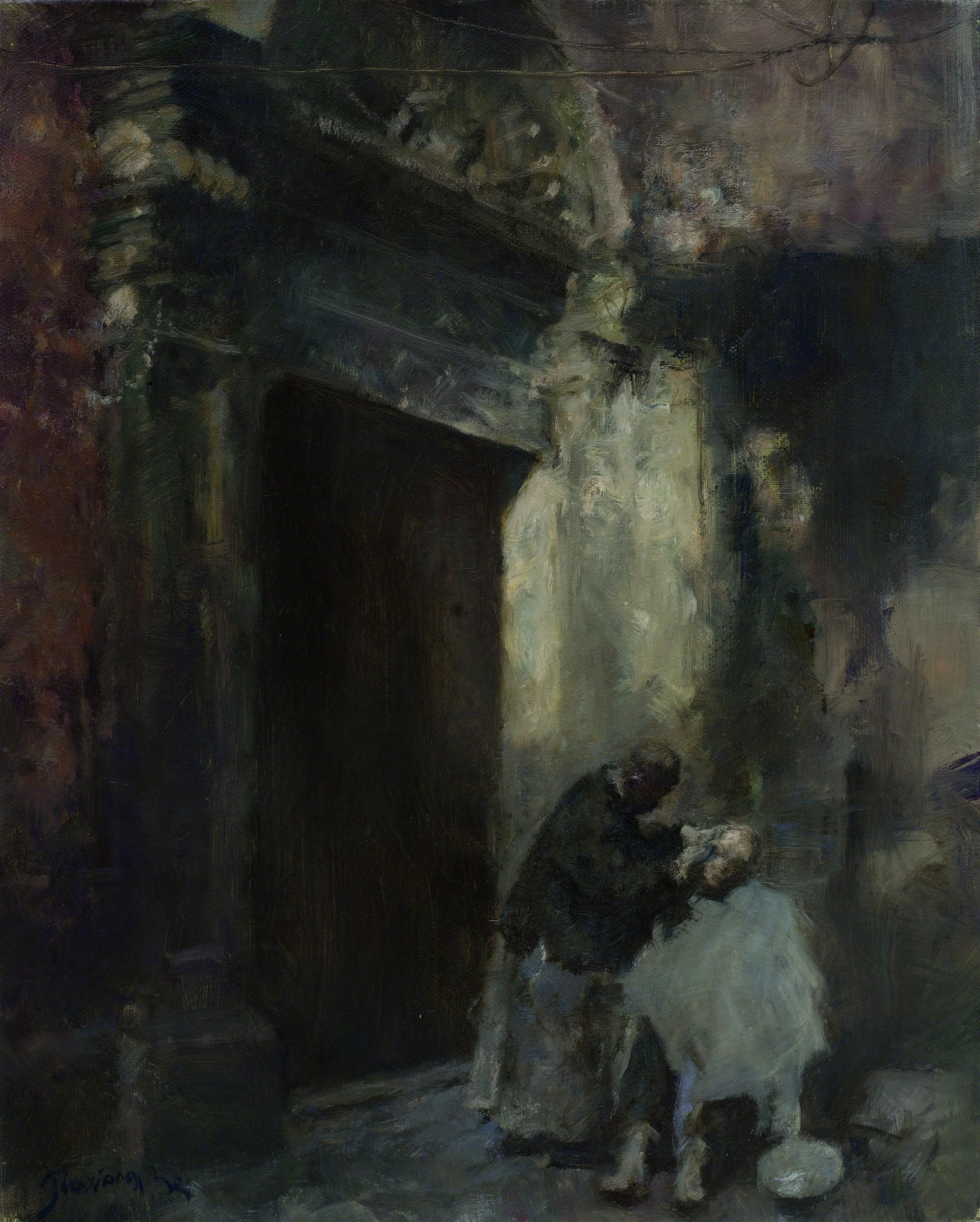

Winter Day

Oil on Canvas

158×103 cm

2016

-

Grand Avenue

Oil on Canvas

410×235 cm

2016

-

Old Time of the Bund

Oil on Canvas

165×172 cm

2019

-

Loaf Around 01

Oil on Canvas

165×172 cm

2019

-

Loaf Around 02

Oil on Canvas

165×172 cm

2019

-

the Steps

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Midday

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Baxian Bridge

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Not Too Bustling

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Afternoon

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

's Up

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Broadway

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Heading Home

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

the East Gate

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

City Pulse

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Pretty Penny

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Street Corner

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Gleaming

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

the Vigorous New Era

-

The Passing of Time

Oil on Canvas

91×72 cm

2023

-

Swelter

Oil on Canvas

91×72 cm

2023

-

Flicking Shadow

Oil on Canvas

91×72 cm

2024

-

Blackish Pink

Oil on Canvas

90×65 cm

2023

-

Out of Oder

Oil on Canvas

90×65 cm

2023

-

Surging Tide

Oil on Canvas

100×80 cm

2022

-

Lost in Lights

Oil on Canvas

91×73 cm

2023

-

Nostalgic Dream

Oil on Canvas

81×81 cm

2022

-

Alleyway Time

Oil on Canvas

81×81 cm

2022

-

Billowing Sunglow

Oil on Canvas

95×74 cm

2024

-

Slanting Light

Oil on Canvas

90×72 cm

2023

-

In the Time

Oil on Canvas

91×73 cm

2022

-

Serenity

Oil on Canvas

95×74 cm

2023

-

Reverie and Hue

Oil on Canvas

95×74 cm

2024

-

Gilding

Oil on Canvas

95×74 cm

2023

-

A City Vignette

Oil on Canvas

91×73 cm

2023

-

Windy Avenue

Oil on Canvas

91×73 cm

2022

-

Blooming Violet

Oil on Canvas

90×72 cm

2023

-

Wandering

Oil on Canvas

91×65 cm

2022

-

First Light

Oil on Canvas

165×120 cm

2025

-

Tranquil Years

Oil on Canvas

165×120 cm

2025

-

Old Days

Oil on Canvas

165×120 cm

2025

-

Sunshade

Oil on Canvas

165×120 cm

2025

-

Fleeting Life

Oil on Canvas

165×120 cm

2025

-

Golden Sunset

Oil on Canvas

165×120 cm

2025

-

Dawn Glow

Oil on Canvas

108×100 cm

2025

-

Flowing Years

Oil on Canvas

108×100 cm

2025

Hide and Seek in the Alley

-

Alley Memories 01

Oil on Canvas

61×76 cm

2015

-

Alley Memories 02

Oil on Canvas

61×76 cm

2015

-

Alley Memories 03 (Collected)

Oil on Canvas

61×76 cm

2015

-

Alley Memories 04

Oil on Canvas

61×76 cm

2015

-

Alley Memories 05 (Collected)

Oil on Canvas

61×76 cm

2015

-

Alley Memories 06 (Collected)

Oil on Canvas

61×76 cm

2015

-

Alley Memories 07 (Collected)

Oil on Canvas

61×76 cm

2015

-

Mengjiang Lane

Oil on Canvas

95×100 cm

2016

-

Anren Lane

Oil on Canvas

95×100 cm

2016

-

Deshan Lane (Collected)

Oil on Canvas

95×100 cm

2016

-

Dexing Alley

Oil on Canvas

95×100 cm

2016

-

Hengfeng Alley

Oil on Canvas

95×100 cm

2016

-

Xiangkang Alley

Oil on Canvas

95×100 cm

2016

-

Chang'an Alley

Oil on Canvas

95×100 cm

2016

the River Flowing in Blood

-

Rivertown 01

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Rivertown 02

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Rivertown 03

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Rivertown 04

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Rivertown 05

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Rivertown 06

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Rivertown 07

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Rivertown 08

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Rivertown 09

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Rivertown 10

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Rivertown 11

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Rivertown 12

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Rivertown 13

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Rivertown 14

Oil on Canvas

126×134 cm

2019

-

Rivertown 15 (Collected)

Oil on Canvas

134×126 cm

2019

Drafts of the Pop-Up Inspirations

-

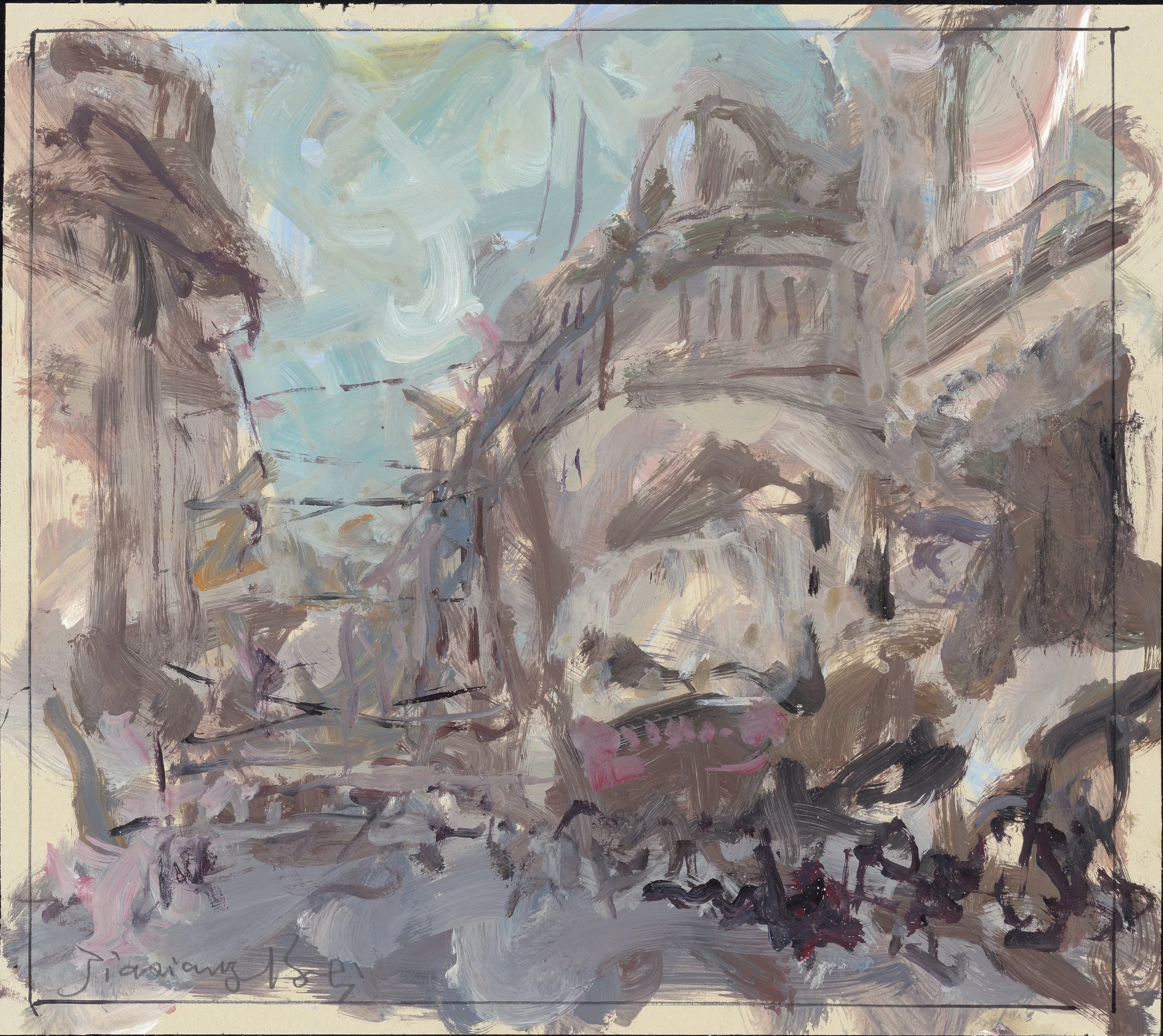

New Era Sketch 01

Propylene on Paper

33×28 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 02

Propylene on Paper

34×28 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 03

Propylene on Paper

34×28 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 04

Propylene on Paper

27×26 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 05

Propylene on Paper

31×23 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 06

Propylene on Paper

28×23 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 07

Propylene on Paper

33×22 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 08

Propylene on Paper

30×25 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 09

Propylene on Paper

30×24 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 10

Propylene on Paper

30×26 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 11

Propylene on Paper

28×25 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 12

Propylene on Paper

33×24 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 13

Propylene on Paper

33×24 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 14

Propylene on Paper

28×22 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 15

Propylene on Paper

30×21 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 16

Propylene on Paper

32×24 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 17

Propylene on Paper

26×24 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 18

Propylene on Paper

31×26 cm

2022

-

New Era Sketch 19

Propylene on Paper

29×33 cm

2022

-

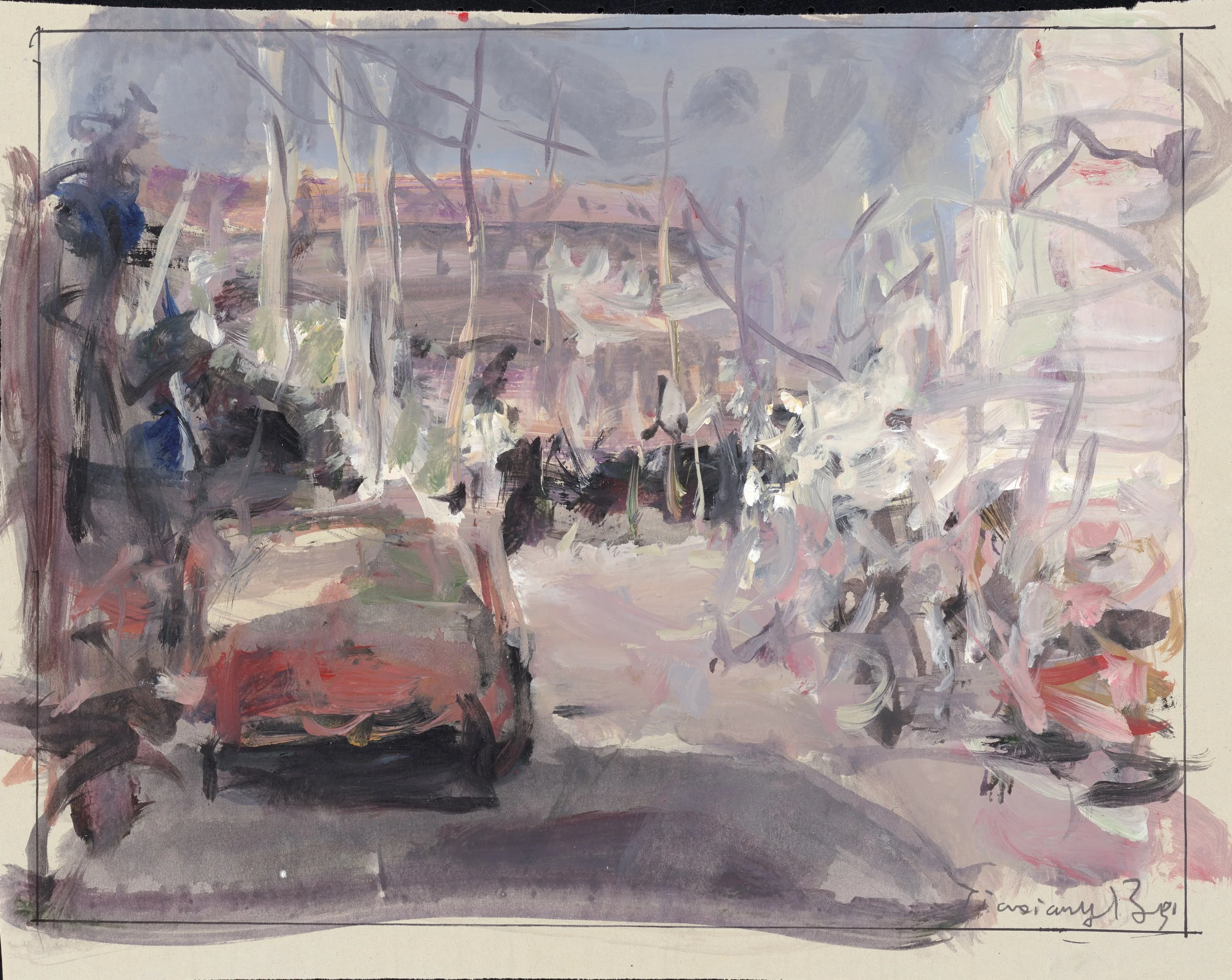

New Era Sketch 20

Propylene on Paper

33×26 cm

2022

Artwork Interpretation

Old Shanghai – Shikumen

In the BEI Jiaxiang’s Alley Maze series, shifts of colour blocks are built upon the foundation of realism to construct the expected imagery. This approach preserves the authenticity of details such as the architectural carvings and water drainage of Shikumen (stone gate) buildings, while the use of hazy grey tones alleviates the sense of triviality. This high concept in painting language not only achieves a visual balance between the concrete and the ethereal but also crystallises the Shikumen as a cultural symbol, articulating a sense of historical memory with restraint.

The symmetry of Shikumen architecture and the depth of the alleyways are transformed in BEI’s work into dialogues across multiple spaces and times. Adopting an aerial perspective, he compresses elements like street-level buildings and dormers into a flattened composition. This echoes the traditional “walled compound” layout of Shikumen while also enhancing the dreamlike quality through the weakening of perspective. The frequent appearances of closed doors contrasted with open kitchen entrances metaphorically represent the dualities of closure and openness, intimacy and community inherent in Shikumen culture.

Compared to Monet’s Rouen Cathedral series, which explores light and colour variations in the same scene, BEI’s method also encompasses multi-angle depictions of Shikumen. While Monet revels in the dance of light and shadows on the complex facades of cathedrals, BEI focuses more on the cultural memories embedded within the architecture. Through repeated reconfigurations of Shikumen building elements, he reconstructs a segment of collective memory belonging to the past.

In the Alley Maze series, BEI Jiaxiang employs this uniquely Sino-Western architectural style to create a dialogue between the spirit of Shanghai School art and Western oil painting techniques, attempting to reinterpret his cultural identity within the context of contemporary art.

Echo from Old Shanghai

In the Shanghai Echo series, BEI Jiaxiang leans towards capturing the macro perspective of Shanghai’s urban landscape and its zeitgeist, rather than focusing on specific architectural forms.

From the textured reliefs of Exotic building clusters to the shimmering surface of the Huangpu River, and the bustling crowds on the streets, BEI meticulously restores architectural details of iconic scenes like the Bund and Nanjing Road. This technique parallels Monet’s The Saint-Lazare Station. Although Monet is more dedicated to the liberation of colour, both artists reveal similar sentiments and subjective projections in their depictions of architectural light and shadow, as well as their memories of the industrial age.

Furthermore, BEI skillfully utilises an overview perspective to compress spatial depth, creating a visual experience akin to the “scattered perspective” found in traditional Chinese scroll painting, echoing the aesthetic tradition of “travelling and observing” prevalent among the traditional Chinese literati, especially in the south-eastern regions. Within the urban fabric, BEI also depicts numerous cars, rickshaws, and bicycles, bestowing a sense of fluidity to the scene and positioning these as the main subjects of “travelling and observing”, forming a dual narrative of grand historical tides and bustling ordinary life.

The essence of the Shanghai Echo series is BEI Jiaxiang’s visual decoding of the “modernity” of Shanghai Art School culture. He neither falls into the trap of documentary realism nor drifts into abstract formalism; instead, he translates Shanghai's monumental landmarks into a visual carrier of Shanghai Art School cultural genes through an imagistic language. This creative path not only continues LIN Fengmian’s ideal of “harmonising Chinese and Western art” but also reconstitutes the possibilities of local narratives from a global perspective—liberating Shanghai from its colonial imagination as “the Paris of the East” and restoring it as a spiritual domain rich in cultural collision.

THE RIVER TOWN SERIES

BEI Jiaxiang’s River Town series oil paintings use the Chinese water towns as their theme, connecting various historical layers through permanent architectural symbols.

His unique “water inked” oil painting language finds rich nourishment in this subject. By diluting oil paints and using palette knife techniques, he simulates the mist engulfing the riverbanks and the rippling water patterns, combining the thick texture of oil paint with the light, permeable qualities of ink wash. While this method resembles WU Guanzhong’s Chinese water town paintings, BEI emphasises the tension between materials—where the viscosity of oil paint meets the fluidity of ink on the canvas. Compared to Western Impressionism, BEI’s brushwork possesses a calligraphic style, often using dry brush strokes to outline forms, echoing the ink techniques in HUANG Gongwang’s Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains.

The River Town series primarily features a palette of blue-grey, dark green, and off-white, creating the unique, moist atmosphere and tranquillity characteristic of Jiangnan. This colour application visually resonates with Whistler’s Nocturne series’ grey-scale aesthetic; however, Whistler’s grey tends towards formalist abstraction, whereas BEI's grey emphasises the visual re-excitation of memory. The blue-gray suggests the natural climate of mist and rain, the off-white conveys the historical wear of crumbling walls, while fragmented warm tones symbolize the lively essence of life in the water towns.

These works essentially represent a cultural return that transcends media. Unlike CHEN Yifei’s romanticized narratives of the Jiangnan water towns, BEI Jiaxiang focuses more on the spirituality and subjective projections of architectural spaces. Through the dialectical fusion of oil paint and ink, he liberates Jiangnan from the clichéd imagery of “small bridges and flowing water”. As SHI Ttao once said, “brush and ink must follow the times,” BEI attempts to recode the poetics of the East through oil painting within a contemporary context.

The Blooming Age

It is the magenta within the canvas that captivates the gaze. This colour serves as the soul of the piece, imbued with the unmistakable imprint of its era, embodying the vibrancy and exuberance of the 1980s that is forever lost. In this context, it represents the eye-catching signs along the streets, the lively atmosphere known to all in the neighbourhood, acting like a lighthouse that suddenly crystallises the scenery drifting through blurred memories into that particular morning.

Such a straightforward personal projection is quite rare in BEI’s work.

A few strokes of magenta instantly transport the viewer back to the golden era of Hongkou, Shanghai, from forty years ago.

The overall composition is woven from blue-green cool tones veiled in elephant grey, where darker areas enhance the layers of the composition, while lighter shades, like potted plants or street trees, infuse the scene with vibrant life. The background’s elephant grey, mixed with soft warm tones and the beige sky in the upper right, creates a hazy morning light. The blue tones in the foreground on the right introduce a sense of complexity amidst tranquillity, rendering the emotional landscape as intricate and elusive as real memories. In this arrangement, the bright tonal foundation lends an ethereal quality that sharpens the details in the foreground.

BEI Jiaxiang’s creation evokes comparisons to Monet’s Haystack series, where visual light and shadow facilitate a transformation from perception to sensation. Monet repeatedly captured light on canvas, striving to freeze that fleeting moment through the interplay of light and shadow. While Monet’s depictions of nature are far more intricate, BEI injects his unique spirit into a similar temporal pause.

Odinary Life

With these considerations, this work creates a space for viewers to engage in personal interpretation. It’s akin to gazing out the window of a swaying train, where quaint village homes and rice paddies slip by like fleeting dreams. Ultimately, what lingers in memory are the individual, unsteady stories that everyone can relate to.

The theme of lane in various series feels like an unassuming path, guiding viewers as they wander through BEI Jiaxiang’s evolving style, picking up clues to understand his artistic language along the way.

In the new series Impression Shanghai, particularly in the work Back to That Day, shadows of his earlier pieces, such as Meng Jiang Alley, De Shan Lane, and Heng Feng Alley, can be seen. Compositional similarities abound, with the focal point often positioned slightly left of centre on the canvas. The right side occupies a bit more space and presents relatively simple content, while the left side reveals more complex details in a smaller area. At the focal point, BEI enhances visual convergence with bright whites that harmonise with the dominant colour palette; whether it’s laundry hanging out to dry or reflections on walls, these moments inject a sense of movement into the otherwise tranquil surfaces.

However, the changes in technique within this work impart entirely different meanings to these similar scenes.

BEI’s new brushstrokes are more spontaneous. As he puts it, the artist “designs less,” allowing the brush to form its unique vitality without constraints. Consequently, his approach to detail is more relaxed; forms often appear vague and free-spirited, yet the flowing nuances naturally create a cohesive spatial and emotional experience. In terms of colour, BEI has incorporated a significant amount of white into his pigments, resulting in an overall low saturation that verges on the unseen in the real world. He substitutes the detail and realism brought by high saturation colours for a more profound sense of depth and richer narrative.

Windy Avenue

Yet, these seemingly disjointed parts of the painting are subtly stitched together by a beam of light created by BEI. This light not only serves to divide the composition and guide the viewer’s gaze—functions that still fall within the realm of “passive” design—but it also represents a subjective projection of the artist’s own emotions. The originally static scene begins to flow under this light, which does not fully adhere to the rules of perspective, transforming into a version from the BEI’s memory.

Compared to the third-person perspectives of street scenes by Pissarro and Sisley, BEI’s series Shanghai Impression is standing on the ground, as if he is one of the pedestrians on the street. Through this authentic viewpoint, he creates an ambiguous moment that exists between reality and memory, showcasing the invaluable “initiative” of the artist.

Romanticism brought natural landscapes onto the canvas, and with the rise of capitalism in Europe during the 16th century, urban street scenes gradually found their way into art. These street views reflect, on one hand, the affluent life of rapid prosperity and, on the other hand, the attempts of the pseudo-intellectuals to approach art through shortcuts. Driven by the art market, street scene painting remained bound to the “commission-based” creative process of Western painting for a long time.

However, in BEI Jiaxiang’s work, this passivity has been completely transcended.

In the lower right corner, two groups of pedestrians are sketched separately in dark and light tones, effortlessly distinguishing between those approaching and those walking away in just a few strokes. Each brushstroke by the BEI is powerful yet deliberately blurs the edges, adding an indescribable dampness to the hustle and bustle of city life. In contrast, the upper left area appears much more transparent. The brushwork slows down, and the tones become purer, with the townhouses conveying a sense of detached tranquillity, as if everything has turned into a state of stillness.

the Vigorous Calm

In the late 19th century, Renoir also created a lot of bright landscapes. His use of colour is incredibly vivid and full of vitality, capturing the joys of life through absolute mastery of light and shadow effects. Coupled with relaxed and confident brushwork, the artist’s subjective emotions are maximised.

Like Renoir, BEI is dedicated to creating simple images amidst a sea of paintings laden with excessive interpretations. These works are unrelated to the changes of the city or the complexities of life, nor are they tied to any particularly significant memories; they simply recreate a momentary, tangible, and understated sense of happiness.

Unexpectedly, this artwork creates a leisurely and quiet scene with its bright tones.

The colour scheme of the painting is dominated by the pink villa in the central area, complemented by a sky blended with pale colours above, evoking the warm glow of a sunny afternoon. The brick-red villa on the left resonates with the grey-green shadows of the trees on the right, adding stability to the composition while enriching the depth of the scene. The bottom of the painting is sketched in a misty blue tone, outlining a few parked cars. This cooler colour suddenly brings a sense of tranquillity, but it quickly becomes lively again with a few touches of soft lavender.

What is most surprising is that the sunlight is bouncing off the car roofs.

BEI Jiaxiang whimsically mixes different shades of yellow paint and loosely applies unblended composite colours in several strokes across the tops of the vehicles, as if playful children were jumping from the left and rolling off the canvas to the right. This technique not only creates a potential dividing line visually but also breathes life into the gentle street scene, adding a playful touch.

Filming by Painting

BEI’s Shanghai storytelling fundamentally embodies the continuance of Shanghai Art School modernity. He replaces precise depiction with expressive brushwork—scraper strokes akin to wild brushwork, and colour blocks pouring like splashed ink. Compared to Ronald Brooks Kitaj’s collage of Jewish anxieties amidst urban chaos, BEI’s fragmented silhouettes, incomplete figures, and shattered neon signs exude a calm nonchalance—an “between real and unreal” aesthetic of Chinese southeast literati tradition. BEI’s work resonates with the modernist spirit of the Shanghai era of the 1920s-30s—allowing oil paint to flow with the breath of ink wash, and reimagining Cézanne’s structures within the brick and tile of Shikumen alleys.

In these reflections on Shanghai, BEI Jiaxiang’s images are never mere reproductions. Instead, they continuously forge a new visual language that fuses Eastern and Western traditions. Mottling bears witness to history; exuberance ignites memories. The fans of oil paint he wields serve as a testament to the indefatigable spirit of the Shanghai Art School’s soul under globalisation. Amidst the depths of layered pigments, an Oriental aesthetic awakens anew with modernity—an enduring testament to the dynamic dialogue between tradition and contemporary expression.

Under BEI Jiaxiang’s brush, Shanghai appears as a dual projection of memory and poetry. Employing oil paint as his backbone and ink wash as his soul, he weaves together the mottled facades of Shikumen houses, the flowing elegance of qipaos, and the vibrant scene of street life into a cross-cultural visual epic across three major themes: Shanghai dialect, Color Realm, and Chinese Fans.

BEI’s creative approach constructs a dialectic between black-and-white austerity and vivid exuberance. Montage-like grayscale tones allow the Clock Tower on the Bund, rickshaw pullers, and alleyway brick walls to oscillate amid the black-and-white chiaroscuro of layered paint scraper strokes. Deep alleyways dissolve in ink-like smoky mist; mottled walls resemble aged photographs emerging from darkness; neon glows blur boundaries like flowing ink. Here, Andrew Wyeth’s sense of cold rural solitude transforms into a virtual-actual dialect in Chinese traditional painting, unleashing an Oriental variation of Post-Impressionism.